Program Description: Multisystemic Therapy® (MST®) is an intensive family- and community-based treatment that addresses the multiple causes of serious antisocial behavior across key settings, or systems within which youth are embedded (family, peers, school, and neighborhood). Because MST emphasizes promoting behavior change in the youth’s natural environment, the program aims to empower parents with the skills and resources needed to independently address the inevitable difficulties that arise in raising teenagers, and to empower youth to cope with the family, peer, school, and neighborhood problems they encounter.

A Master’s-level therapist works with the family to identify strengths and weaknesses in the adolescent, the family, and their transactions with other systems (e.g., peers, friends, school, parental workplace). Identified problems are targeted for change by using the strengths within each system to facilitate change. Intervention approaches are derived from well-validated strategies such as strategic family therapy, structural family therapy, behavioral parent training, and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Typically, MST uses several types of interventions during the course of the 3- to 5-month program. Individual-level interventions generally involve using cognitive behavior therapy to modify the adolescent’s social perspective-taking skills, belief or motivational system, and ability to deal assertively with negative peer pressure. Family-level interventions aim to remove barriers to effective parenting, enhance parenting competencies, and promote affection and communication among family members. Interventions might include introducing systematic monitoring, reward, and discipline systems; prompting parents to communicate effectively with each other about adolescent problems; problem solving day-to-day conflicts; and developing social support networks. Peer-level interventions frequently aim to decrease affiliation with delinquent and drug-using peers and to increase affiliation with prosocial peers. Interventions in the school domain may focus on establishing positive lines of communication between parents and teachers, parental monitoring of adolescent’s school performance, and restructuring after-school hours to support academic efforts.

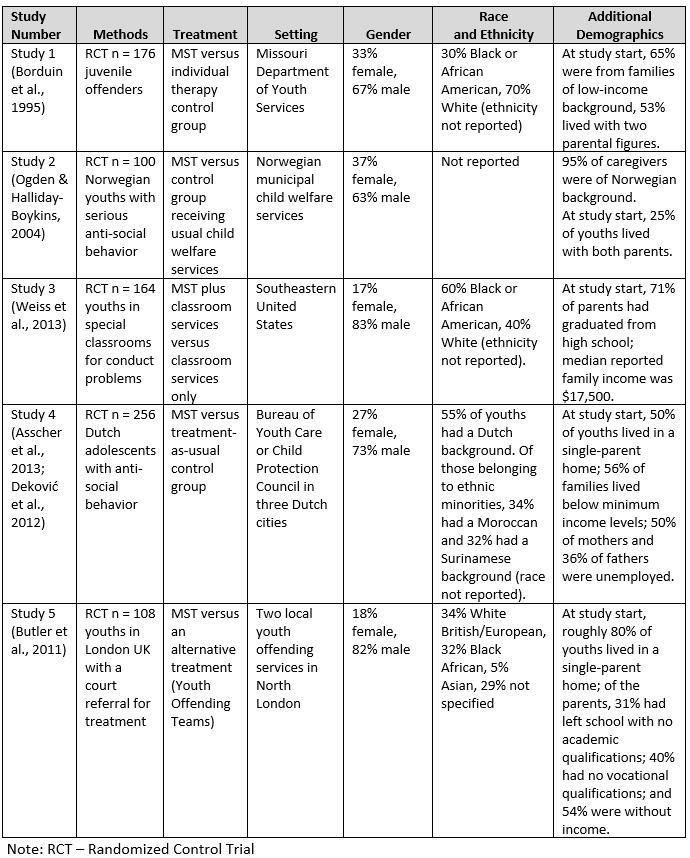

Results: Blueprints has certified five studies evaluating Multisystemic Therapy. A summary of the study demographics is as follows (see Table 1):

- The samples included youths with serious behavior problems.

- Study 1 was done by the developer; Studies 2-5 were conducted by independent researchers.

- Most youth were male (reported in binary male/female categories).

- Two studies were conducted in the U.S. (Missouri, and SE states); 3 were in Northern Europe.

- Race, ethnicity, and income were mixed. In terms of race, for the two U.S. studies, one sample was 30% Black or African American and 70% White, and the other sample was 60% Black or African American and 40% White.

Study 1: Borduin et al. (1995) randomly assigned 176 adolescents referred through the State of Missouri juvenile courts to the intervention group (n=92) or an individual therapy control group (n=84). Adolescents and parents completed pretest and posttest assessments that included self-reports and observational tasks. Additionally, arrest data was obtained approximately four years after program completion from police and court records. Compared with the control group at posttest, MST youth experienced significantly decreased parent-reported problem behaviors and improved family relations per the youth, parents and observations. By four years post intervention, the intervention group had fewer arrests (including violent arrests).

Study 2: Ogden and Halliday-Boykins (2004) randomly assigned 100 Norwegian youths with serious antisocial behavior to an intervention group (n=62) or a control group receiving child welfare services (n=38). Assessments at posttest and two-year follow-up measured problem behavior, delinquency, and out-of-home placement. The intervention group, relative to the usual-services control group, showed significantly decreased youth internalizing symptoms at posttest.

Study 3: Weiss et al. (2013) conducted a study in the southeastern U.S. in which they randomly assigned 164 youths enrolled in behavior intervention classrooms to MST (n=84) or to a treatment-as-usual control group (n=80). Assessments from posttest to a one-year follow-up measured conduct problems, externalizing, and criminal offending. Youth in the intervention group showed significantly lower parent- and youth-reported externalizing and fewer absences in school compared with youth in the control group.

Study 4: Deković et al. (2012) and Asscher et al. (2013) randomly assigned 256 Dutch adolescents with antisocial behavior to an MST intervention group (n=147) or a treatment-as-usual control group (n=109). Assessments at pretest and posttest measured a variety of outcomes relating to antisocial behavior and family relations. Relative to the control group, the intervention group showed significant reductions in externalizing, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder and property offenses as well as improved parent-child relationship quality.

Study 5: Butler et al. (2011) randomly assigned 108 adolescents referred by youth offending services in London, England, to an MST intervention group (n=56) or a treatment-as-usual control group (n=52). Assessments from posttest to 12 months post intervention measured reoffending and problem behavior. Relative to the control group, the MST youth showed a significant decrease in non-violent offending, aggression, delinquency, and psychopathic traits.

Table 1: Summary of Sample Demographic Characteristics

References:

Study 1:

Borduin, C. M., Mann, B. J., Cone, L. T., Henggeler, S. W., Fucci, B. R., Blaske, D. M. & Williams, R. A. (1995). Multisystemic treatment of serious juvenile offenders: Long-term prevention of criminality and violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 569-578.

Study 2:

Ogden, T., & Halliday-Boykins, C. A. (2004). Multisystemic treatment of antisocial adolescents in Norway: Replication of clinical outcomes outside of the US. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 9(2), 77-83.

Study 3:

Butler, S., Baruch, G., Hickey, N., & Fonagy, P. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of Multisystemic Therapy and a statutory therapeutic intervention for young offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(12), 1220-1235.

Study 4:

Asscher, J. J., Deković, M., Manders, W. A., van der Laan, P. H., Prins, P. J. M., & the Dutch MST Cost-Effectiveness Study Group 4. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of Multisystemic Therapy in the Netherlands: Post-treatment changes and moderator effects. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9, 169-187.

Deković, M., Asscher, J. J., Manders, W. A., Prins, P. J. M., & van der Laan, P. (2012). Within-intervention change: Mediators of intervention effects during Multisystemic Therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(4), 574-587.

Study 5:

Weiss, B., Han, S., Harris, V., Catron, T., Ngo, V. K., Caron, A., . . . Guth, C. (2013). An independent randomized clinical trial of Multisystemic Therapy with non-court-referred adolescents with serious conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 1027-1039.

Read the Program Fact Sheet